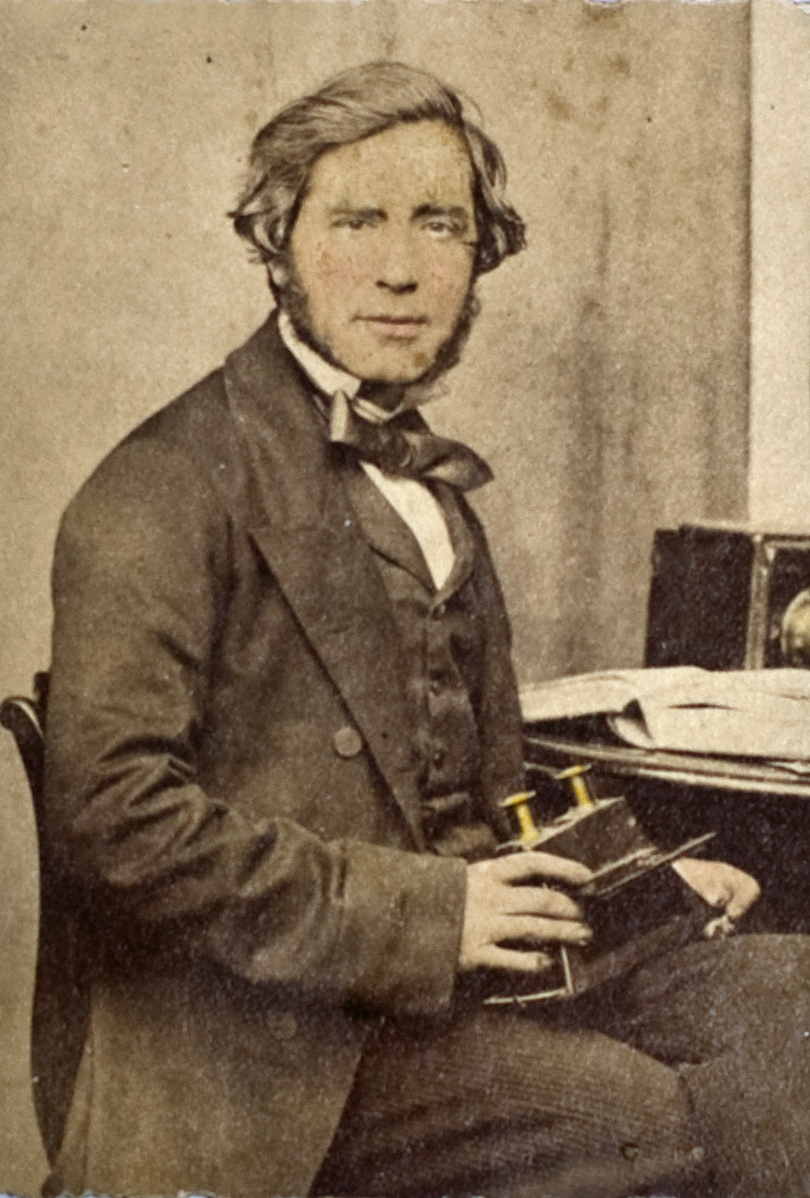

William Paul Dowling (1824-1877)

The official family website for an Irish Patriot and Portrait Artist

This site was establihed in 2021 with factual reference to the Dowling family archive and other historical records from the nineteenth century.

Errata: An article published in the Australiana Magazine, November 2020, falsely challenges the established date of birth for William Paul. The author postulates that William was the son of "Peter" born two years earlier and the baptism was incorrectly entered in the Church records! This inadequate research contradicts Dowling Family records and many official 19th century legal records, in London and Tasmania. The article then conjectures that he was another William Dowling that attended a school outside the city of Dublin at a junior level but at the same time was receiving prizes in his final year from the Royal Dublin Society Art School. There are other items presented in the article which are considered improbable. - EFOD May 2021

The story of an artist, a photographer, a patriot,

devoted husband and father.

William Paul Dowling was one of eight chidren, and

seventh child of Bernard Dowling (1779-1846) and Marcella (nee McEver)

(1780-1827). Bernard was an Attorney and his son, John Bernard born in 1820, was

apprenticed to his father and also destined for a career in law. The younger

William Paul was born in 1824. He studied art at the Royal Dublin Society and is

on record for winning prizes for landscape in pencil and “drawing in the round”

which would most probably have been life drawing. Though he is described in an

obituary as a gentle quiet man he must have been a colourful personality in

middle-class Dublin, in the early 1840’s. He would have then known his future bride,

Julianna De Veaux, the daughter of a Dublin Merchant.

His family had a keen interest in Irish Nationalism but

we don’t have many details of William's involvement in politics in Ireland prior

to going to England in 1845. His move

to London was to take up lucrative employment as a draftsman in the railway boom

and at the same time establish himself as a portrait painter. He joined the

Davis (Confederate) Club in 1848 and became secretary. This in turn led to an

invitation to join the Chartists’ committee who were becoming more active and

rebellious. He was arrested in Lambeth Walk in August 1848, brought before Bow

Street Court and charged with treasonable conspiracy.

Evidence was given that papers were found in his lodgings

which proved his involvement with the Chartists including a letter to his sister

in Dublin. The judge ordered that Dowling be remanded so that his case would be

considered along with other Chartists in custody. Much was happening in Europe

at that time with the famine in Ireland and the concern of the English

Parliament of uprising and the movement for suffrage. This gave rise to the

enactment of “The Crown and Government Security Act” which made assembles of

people unlawful and created seditious offences which were felonies and not

punished by death sentence. The trial of fifteen chartists was held in September

1848 and William Paul Dowling was represented separately by Edward Kenealy. It

is reported in the State Trials and also described in Kenealy’s autobiography

who questions the whole legal procedure. The chief witness for the Crown was the

despised informant William Powell “Lying Tom” who using the name Johnson and

pretending to be a Chartist had attended their meetings and reported proceedings

to the police who in turn paid him £1 per week for subsistence. The chartists

were found guilty and William Paul was sentenced to be deported

for life. Whilst the new Act for unlawful assembly saved his neck the subsequent

transportation brought sadness and tragedy to his family and his frail lineage

died out.

The prosecuted Chartists were kept at Newgate for a year

under the difficult prison conditions of the time. In a guarded letter to his

family in Dublin (taking care not to identify any other person who might become

a target) William tells how his pencil has been kind to him, spending his time

doing portraits of his fellow thirty five prisoners, and being excused from

other unpleasant chores. He speaks well of the courtesy of the Prison Staff many

of whom probably would have identified with the Chartist claim for suffrage.

However, to understand the politics of the day and despite the passing of the

“Crown and Government Security Act” there was a body of the ruling ascendency

who considered that anyone agitating for a vote for all men should sent to the

gallows.

William Paul was one of three hundred convicts to sail on

the Adelaide to Van Diemen’s Land and arrived in Hobart Town in November 1849.

Only one convict died under the captaincy of surgeon Frederick Le Grand and

forty disembarked in Hobart. The remaining two hundred and forty seven arrived

at Sydney on Christmas Eve and were actually the last convicts deported to New

South Wales.

The family is fortunate to possess letters written by

William Paul to his brothers and sisters from his arrival in England in 1845 and

up to 1875 from Australia. Another letter in August 1877 from Julianna describes

her father’s passing moments. There is also a good body of information in

Tasmanian Archives relating to his work as an artist and photographer.

William Paul was granted a ticket of leave on arrival as

he was considered a gentleman and capable of supporting himself. This “parole”

gave him permission to get married. His sweetheart from Dublin quickly arrived

and they married in 1850 in St. Joseph’s Chapel where two large religious

paintings, possibly his best surviving, still hang today. He was a devout

Catholic as can be seen in his letters and his daughter’s description of his

death. He took trouble to establish separate lodgings for his wife-to-be before

their marriage. Whilst influential supporters made representations lobbying for

the successful 1854 pardon given to William Smith O’Brien, leader of the 1848

rebellion, there was no such support offered for Dowling. It is suggested that

the Young Ireland Movement did not approve of William Paul’s involvement with

the Chartists and indeed Smith when returning to Ireland visited Hobart and

expressed his apology that he had not been so included. Dowling himself

subsequently applied and was granted a conditional pardon in 1855 and a full

pardon in 1857.

It is told in the family that many letters from William

Paul were destroyed for censorship reasons, possibly to hide references to

womanly matters as Julianna endured bad health and sadly lost many children.

Equally they may have been too sad and tearful but also it has been suggested

some may have referred to artistic descriptions of shapely women and that

certainly would not have received approval from the womenfolk in Dublin!

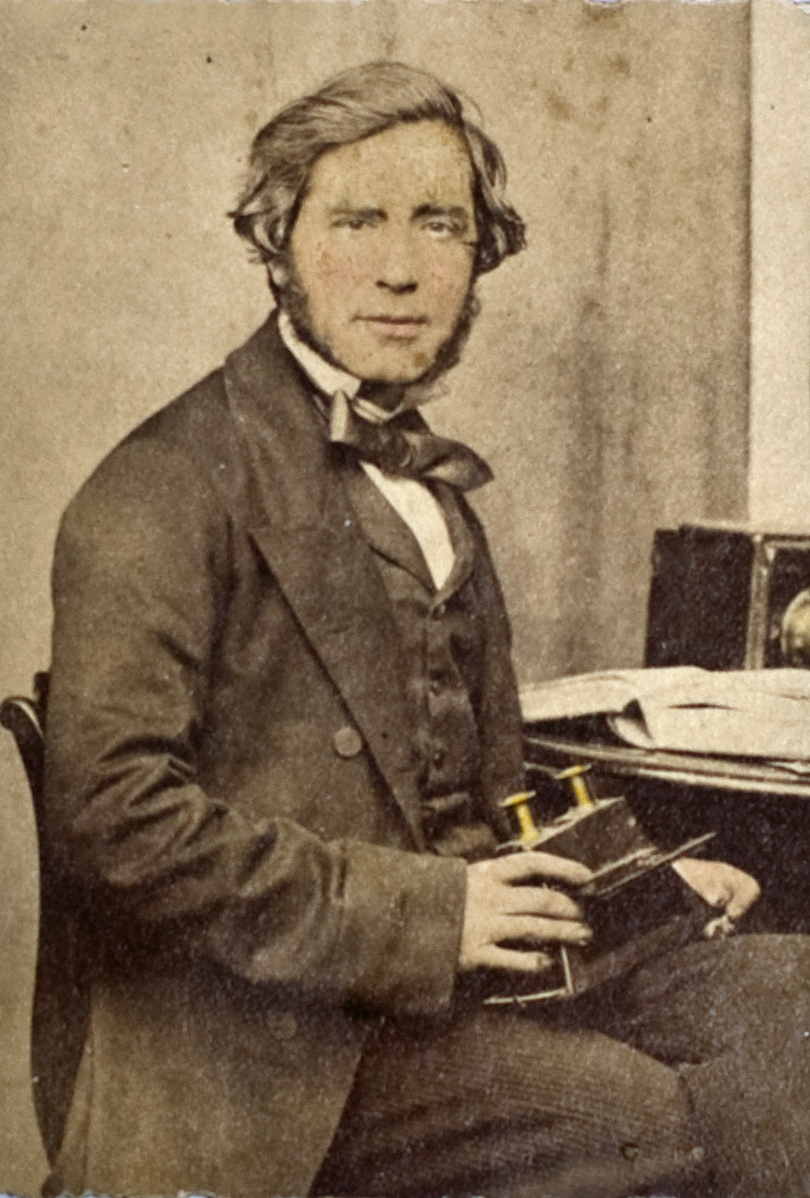

It can be seen from the correspondence that William Paul

was very proud and fond of his children. Their known first born was Julianna

called after her mother and affectionately called Nannie. Her birth date

suggests that there may have been an older child who died in infancy. We know

that four of the babies did not survive.Julianna was only sixteen when her mother died in 1869.

She would have seen her mother lose four children in infancy, her next brother,

Henry Emmett, at fourteen years and her youngest, Bernard, at the age of twenty

two.When her mother died in 869 Julianna joined the newly established order of

the Sisters of St Joseph under the care of Fr Julian Woods, a Passionist priest

who had arrived from England three years earlier. At one time she was the

Organist at the Church of the Apostles in Launceston but moved around a number

of locations teaching music. She was very close with her father and was beside

him when he died of tetanus in 1877. She suffered a stroke around 1910 and was

an invalid at Lochinvar Convent, NSW, until her death in 1922. It is said she

regularly corresponded with her Aunt Charlotte, wife of John Bernard, keeping

alive the family connections to Dublin. Even as an invalid, Sr Mary John

continued to assist in the teaching of music at Lochinvar.

It can be seen from the correspondence that William Paul

was very proud and fond of his children. Their known first born was Julianna

called after her mother and affectionately called Nannie. Her birth date

suggests that there may have been an older child who died in infancy. We know

that four of the babies did not survive.Julianna was only sixteen when her mother died in 1869.

She would have seen her mother lose four children in infancy, her next brother,

Henry Emmett, at fourteen years and her youngest, Bernard, at the age of twenty

two.When her mother died in 869 Julianna joined the newly established order of

the Sisters of St Joseph under the care of Fr Julian Woods, a Passionist priest

who had arrived from England three years earlier. At one time she was the

Organist at the Church of the Apostles in Launceston but moved around a number

of locations teaching music. She was very close with her father and was beside

him when he died of tetanus in 1877. She suffered a stroke around 1910 and was

an invalid at Lochinvar Convent, NSW, until her death in 1922. It is said she

regularly corresponded with her Aunt Charlotte, wife of John Bernard, keeping

alive the family connections to Dublin. Even as an invalid, Sr Mary John

continued to assist in the teaching of music at Lochinvar.

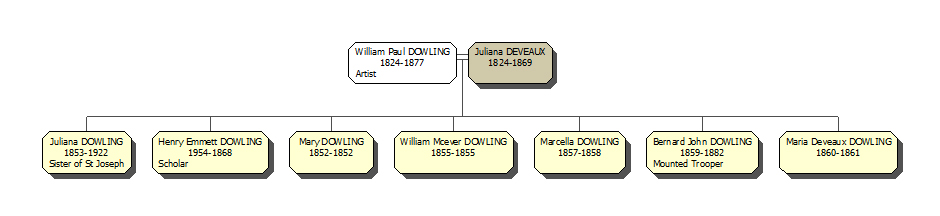

In a letter to his brother John, William Paul proudly

speaks of young Harry being dressed in his first set of breeches. The same letter mentions his wife’s poor

condition and being confined to the bed. Her poor health is regularly mentioned

in letters right up to her early death and is a reminder of the continuing

emotional hardship in the household. But William had great hopes for his eldest

son who was brought up in a home of serious education and “kept at his books”. His father wrote that the young teenager was proficient

in Euclid, Ceasar, Greek and fluent in French and with pride was sending his

young son to Ireland for further education and to become an Irishman of his

dreams. Henry Emmett Fitzgerald Dowling died at sea on journey home to Tasmania

in 1868 at the tender age of fourteen.

In a letter to his brother John, William Paul proudly

speaks of young Harry being dressed in his first set of breeches. The same letter mentions his wife’s poor

condition and being confined to the bed. Her poor health is regularly mentioned

in letters right up to her early death and is a reminder of the continuing

emotional hardship in the household. But William had great hopes for his eldest

son who was brought up in a home of serious education and “kept at his books”. His father wrote that the young teenager was proficient

in Euclid, Ceasar, Greek and fluent in French and with pride was sending his

young son to Ireland for further education and to become an Irishman of his

dreams. Henry Emmett Fitzgerald Dowling died at sea on journey home to Tasmania

in 1868 at the tender age of fourteen.

The only other child to live into adulthood was the

youngest boy Bernard who by the letters we know as having been wild and not

serious about education. His father at one point implored him to give up his

life as a sailor and return to education. He however left Tasmania for the

mainland of Australia and lost his twenty two year life by a horseback accident

as a mounted trooper in 1882.

The only other child to live into adulthood was the

youngest boy Bernard who by the letters we know as having been wild and not

serious about education. His father at one point implored him to give up his

life as a sailor and return to education. He however left Tasmania for the

mainland of Australia and lost his twenty two year life by a horseback accident

as a mounted trooper in 1882.

But there are more stories that bring home the reality

and hardship of travelling to far-off Tasmania that William Paul had to endure.

He saw the promise of good weather and business opportunity as something to

attract both his brother and sister to Australia.

There was great excitement in the Dowling home with the

prospect of William’s sister Anne expected at Christmas 1854. She had boarded in

London on September 12th and William Paul went out by small boat to

meet the ship to greet his sister. He describes the day of rising excitement

shattered by the news Anne had died of cholera and was buried at sea.

William practised as a portrait artist both in Hobart and

later in Launceston. The potential market for sitters was limited in the convict

colony of Tasmania so he reluctantly took up the parallel profession of the new

studio method of photography. He described it as “foe-to-graphic” a phrase he

attributes to the artist Edwin Landseer.

William Paul also corresponded with his younger brother

Mathew, known as Mat, who was born in 1826. William encouraged him to take up

this new art of photography and join him in Tasmania in business there. They did

practise together for a while as the Dowling brothers but Mat broke out and

established his own studio. By what is known Mat must have been a difficult and

argumentative person. He stayed with his brother and sister-in-law Julia but

would not converse with her a table. This went on for many months and Mat

steadfastly refused to change his ways. It caused William and Julia much

sadness. William also used his artistic skills to colour in photographs. There

is nothing on record to show that Mathew left descendants in Australia.

When William Paul received his full pardon they planned

as a family to return to Dublin which happened around 1865. He was given a

hero’s welcome by the family. He established a studio in Lincoln Place for a few

years but needed to return in 1868 to the better climate in Tasmania for the sake of

Julia’s poor health.

Ten years later John Bernard’s delicate son,

William Paul's nephew, James was

also enticed to come to Tasmania but he arrived in 1877 to find his uncle had

just died and the home-place had disbanded. He boarded with Mr & Mrs Roper who

had been friends of the Dowlings and worked as a book-keeper for Mr J Ellis. He

died of consumption in Launceston.

Ten years later John Bernard’s delicate son,

William Paul's nephew, James was

also enticed to come to Tasmania but he arrived in 1877 to find his uncle had

just died and the home-place had disbanded. He boarded with Mr & Mrs Roper who

had been friends of the Dowlings and worked as a book-keeper for Mr J Ellis. He

died of consumption in Launceston.

Daughter Julianna describes being at her father’s bedside

when he died in 1877. Seemingly he was a religious man and his death was

peaceful and with prayer. He died of tetanus following surgery. The Catholic

Standard concluded its obituary : “The deceased was a devoted Irishman and a

sincere Catholic, honourable to the letter, and ever ready to lend a helping

hand to the needy, he was respected by all classes of the community.”

Letters

In

2005 The Tamanian Historical Research Association published "Letters of an Irish

Patriot" edited by Margaret Glover and Alf MacLochlainn, based mainly on

letters and other archives kept by the family in Dublin. The letters

give a wonderful insight into the life of an exiled portrait artist in the mid nineteenth century.

In

2005 The Tamanian Historical Research Association published "Letters of an Irish

Patriot" edited by Margaret Glover and Alf MacLochlainn, based mainly on

letters and other archives kept by the family in Dublin. The letters

give a wonderful insight into the life of an exiled portrait artist in the mid nineteenth century.

from Dowling Family Archives - EFOD - May 2021